Reckoning

A year ago, I didn't know their names. I knew my great-grandfather's name was Walter and that was about it. I knew he married a girl with a French name—French Canadian, it turns out. And that their son married a girl whose parents emigrated from Sicily to America. Immigrants all around.

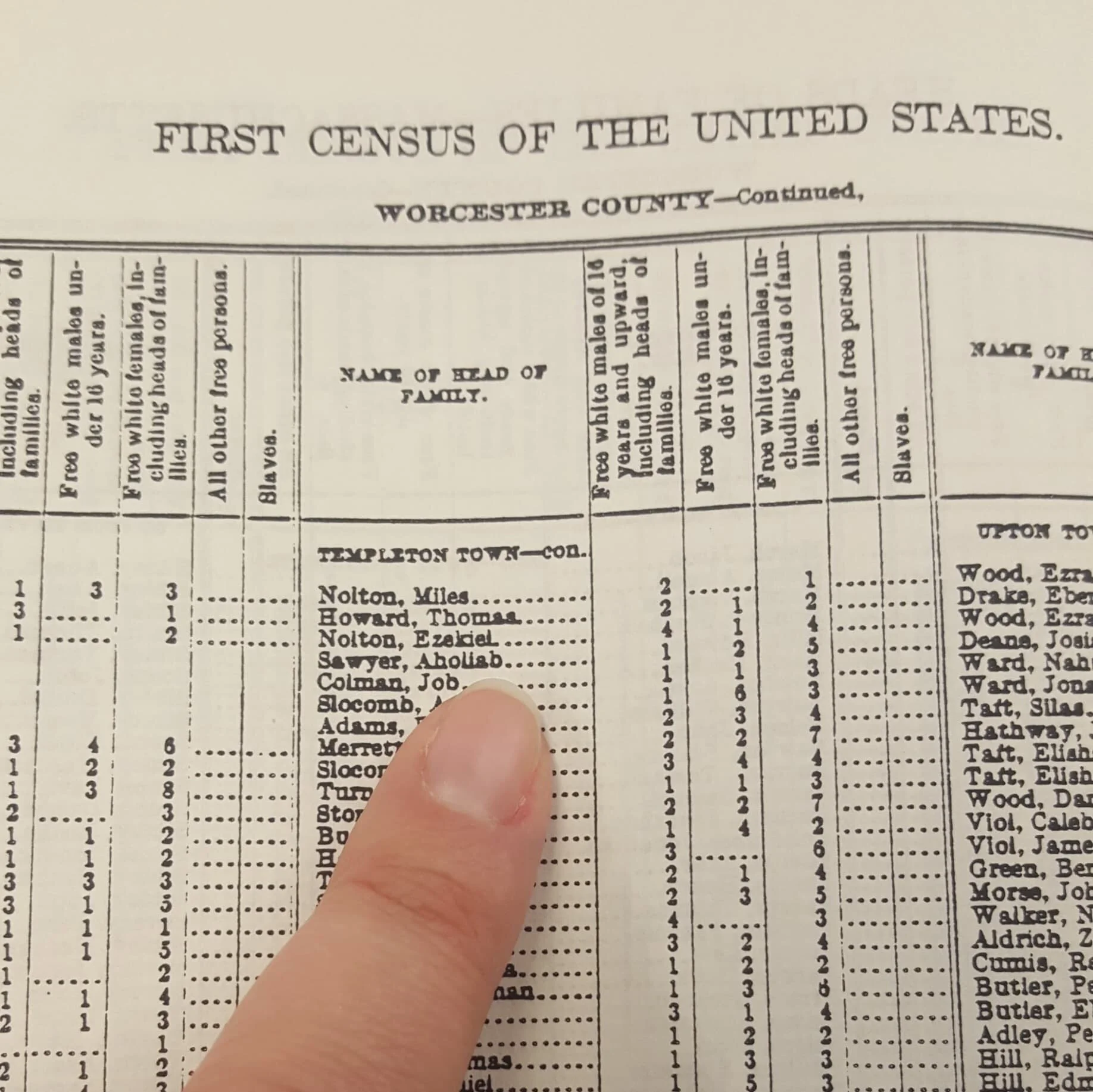

But all it takes is one—one who was born here, who came from people born here, who came from people born here. The paper trail led me back and back and back, until I found Aholiab Sawyer, my 5x great-grandfather, on the First Census of the United States—a resident of Templeton, Massachusetts. I was STUNNED. I had spent so many years researching and relating to my Sicilian immigrant heritage that I experienced some kind of cognitive dissonance upon realizing I also had ancestors who went back to the 1700s in America, in Massachusetts. In Templeton!

The depth of information I have found has been both incredibly valuable from a genealogy standpoint,and incredibly rattling from a historical standpoint. The fact that documentation even exists for this line of my family is testament to their European whiteness, their English roots, a privilege I can neither deny nor ignore. That the paper trail led me to a graveyard, to a stone I could touch, to an inscription I could read, allowing me to acknowledge my ancestors in a very tactile way, is another privilege of their—my—whiteness.

And it didn't stop there. When I started to research the history of my little hometown, which had tripled in 25 years to a whopping 950 residents during that first census, I learned that like many other towns of the era, the land was promised to militiamen (or their heirs) who had "cleared the land" of indigenous peoples decades earlier. This plot of land was named the Narragansett Plantation Number 6, believed to be part of the tribal migration lands used by the Narragansett tribe who is currently associated with lands of southern Rhode Island. My ancestors either indirectly benefited from that violence by taking ownership of land that was taken from others, or worse—they directly benefited because they were the ones inciting the violence. The mere possibility takes my breath away.

These last months, since finding this information, I have been sitting with it and using it to understand my personal responsibility to share these facts and make amends for what my ancestors have done. It has caused some kind of reckoning for me, in realizing I had insulated myself from any colonizer guilt by identifying with my recent immigrant forebears. Despite my awareness that all my other ancestors who migrated to this land did so in the 1800-1900s—well after most of the atrocities and violence occurred on this soil—there is also a line of ancestors who preceded and participated in those atrocities. It is my duty and my obligation to acknowledge this.

I have researched which other tribes also used that land as part of their seasonal hunting grounds. I have looked at old maps drawn by white men, with anglicized tribal names penciled in over borders defined by other white men. It wasn’t just the Narragansett: the Nipmuc, Pennacook, Wampanoag, and Massachuset tribes may have also roamed the lands of what is now called Templeton; those tribes may also have been chased away or murdered in the name of colonization. The Wampanoag, who as I write this are fighting to prevent their reservation lands in Mashpee from being disbanded by the federal government.

I know for a fact that I have more work to do here. This is just the beginning of this reckoning. As amazed as I am at finding my own direct ancestor’s name in the First Census of the United States, I cannot share that fact without acknowledging how his name got there, and the distinct privilege of whiteness that exists by it being recorded anywhere at all.